Open Innovation in Blue Bioeconomy – a knowledge-driven economy approach

Due to the current technological state of the art, the world is tending towards a knowledge-driven economy. According to the Global Knowledge Index (GKI) from Knowledge4All (1), Portugal ranked 27th (61.8 GKI) amongst the countries with the higher GK indexes, and only 10 points below the 1st rank- Switzerland (71.5 GKI). However, when you consider the population variable, a dilution of innovation potential is felt, and Portugal drops to 34th place (1).

Europe is still the second most innovative region in the world and, according to the European Innovation Scoreboard (EIS), from 2020 to 2021 Portugal dropped from strong to moderate innovator (2). These reports positively detailed Portugal’s innovators, innovation-friendly environment, attractive research system, SMEs innovating in-house, broadband penetration, and SMEs with product or process innovations (2). On the other hand, Portugal reported handicaps were in-house business process innovators, innovators that do not develop innovations themselves, scarce exports of knowledge-intensive services, low R&D expenditures in the corporate sector, small co-funding of public R&D expenditures, and infrequent public-private co-publications. Nevertheless, Portugal is above the European Union average in enterprise births (10+ employees), total entrepreneurial activity, and foreign direct investment net inflows, which translates to valuable potential.

In this article, we will not focus on the reasons why Portugal is lagging on the construction of a knowledge-based society to propel innovative development and economic growth since, as shown above, it is a multifactorial complex problem. Rather, we will focus on open innovation as a driver of economic growth and will present the main reasons for applying it to the Blue Bioeconomy Sector.

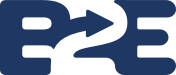

Innovation, as defined in ISO 56000:2020 (3), is the practical implementation of ideas that result in the introduction of new goods or services or improvement in offered goods or services. Traditionally, innovation happens in a vertical closed structure within a corporation. Research and development of novel products and services are made in-house, kept secret, and posteriorly, in due course, some are presented to the market. This process suffers from a natural intrinsic bias, overlooking competitors and sometimes the market, and has additional disadvantages that will be addressed below.

Henry Chesbrough was the first to break the innovation paradigm with the introduction of the concept of open innovation (OI) in 2003 (4), and since then it has naturally evolved to a model where companies use external as well as internal ideas and paths to market, using pecuniary and non-pecuniary mechanism aligned with their business model towards technological advances of their products, process or services gaining a competitive collaborative advantage. This innovation permeability ultimately results in impacts at the level of the consumer, the corporation, the industry, and the society (Figure 1).

OI implementation requires a corporate mindset shift based on experience, knowledge, and technology sharing within and outside the company boundaries. The key to success during implementation is to focus on diversity and getting to know the available innovation ecosystem. Internal team diversity, collaboration and cocreation with external R&D institutions and companies, connection with innovative start-ups, hackathons, think tanks, and crowdsourcing organizations, and involvement with local, regional, and international innovation hubs, are some of the possible actions in this open innovation implementation journey.

So far OI is still considered by some as a paradigm when it comes to Intellectual Property (IP) management, and a legal nuisance not worth the trouble. However, some of the world’s biggest patent applicants, Philips NV, IBM, and Intel, have embraced OI as a strategic shift and upon analysis of their patenting activities, no deleterious effects are observed (5, 6), and, in some cases, the number of applications has increased. These companies have stepped up their innovation game to accommodate extensive information exchange of and with their collaborative partners (competitors and R&D institutions) and manage collaborative relations accordingly, so as to not jeopardize their or their partners’ IP.

Open and collaborative innovation requires corporations to get involved in the governance of IP more actively and strategically, not just in terms of acquiring and defending them, but also to use the rights and generate royalty. Conveying inventive ideas, whether in a formal or informal format, destroys novelty in a patent application, therefore, caution should be taken regarding sharing and disclosing information within OI, and collaboration agreements should clearly regulate this aspect.

Although managing knowledge outcomes in a new open collaborative research and innovation ecosystem is challenging, IP will overcome inaccuracy in the definition and scope of the knowledge or technology to be developed collaboratively, hence aiding the structure of a collaboration agreement. A patent or another IP right, being a legal document presents all the correct language to be used in licensing agreements and can be used as a negotiation and litigation mitigation tool with a third party that holds complementary technology. Furthermore, licencing agreements with third parties encourage the further development of a technology that otherwise would linger to enter the market or would not see a different valuable application in different markets.

The benefits of OI via collaborative projects could be summed up as an increase in networking and a decrease in investment/costs, risk, and time-to-market, however, there are far greater ones. Cocreation, results, and technology dissemination generate novel ideas for products, create new markets for disruptive technologies, and promote novel business models and companies.

The European Commission has stated that “to cope with an increasing global population, rapid depletion of many resources, increasing environmental pressures, and climate change, Europe needs to radically change its approach to production, consumption, processing, storage, recycling and disposal of biological resources” (7). Due to the pressing global challenges, OI projects are the most adequate instruments to achieve novel solutions, and aquaculture and blue biotechnology, the pillars of Blue Bioeconomy, are considered strategic (7).

The versatile Blue Bioeconomy food products contribute to the mitigation of the increased protein demand trend, improve food security, food safety, and human health without depleting natural resources, while, in some cases, sequestering C02 from the atmosphere. The high potential non-food Blue Bioeconomy products, wholly or partly derived from materials of biological origin, include pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, chemical building blocks, lubricants, detergents, inks, fertilisers, textile, furniture, bioplastics, biofuels, and bioenergy.

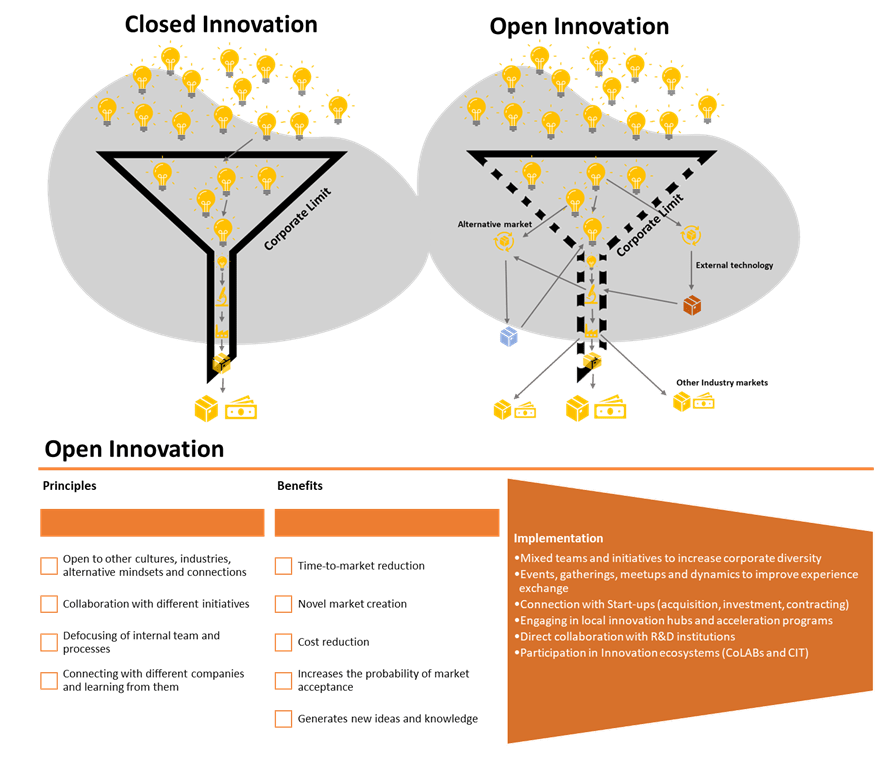

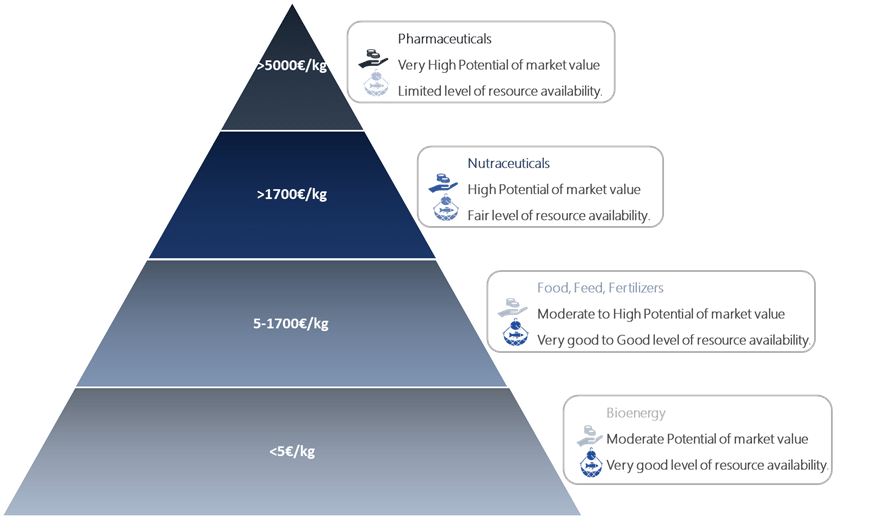

Blue Bioeconomy Collaborative projects can render diverse novel value-chains and market entry of innovative sustainable products while at the same time aiming to monetize technologies applicable to different fields (8) The Kg of produced biomass has tremendous monetization potential (Figure 2), and its total usage is paramount (9).

To accomplish circular, zero waste, economically viable processes, OI approach to all Blue Bioeconomy byproducts should be employed (Figure 3). Recently, in Portugal, a multidisciplinary Consortium was established and funded, based on OI principles, aiming to reindustrialize national industries through the incorporation of blue biotechnology products in their value chains (10). This is the time for a Portuguese corporate mentality shift, and the results and impact of this OI endeavour will be concluded by the end of 2025. Exciting times ahead!

References:

- Knowledge4All (2021) Global Knowledge Index; Knoema.

- European Commission (2021) European Innovation Scoreboard: Innovation performance keeps improving in EU Member States and regions; Press release; Brussels.

- “ISO 56000:2020(en)Innovation management — Fundamentals and vocabulary

- Chesbrough HW (2003) Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology; Harvard Business School Press; Boston, Massachusetts; USA

- European patent office (2020). Patent Index 2020; Munich; Germany

- European patent office (2021). Patent Index 2021; Munich; Germany.

- European Commission. (2012). Innovating for Sustainable Growth: A Bioeconomy for Europe, Communication. Brussels.

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (2019) Blue Bioeconomy Forum- Roadmap for the blue bioeconomy, Brussels.

- Barbier M, Charrier B, Araujo R, Holdt SL, Jacquemin B, Rebours C (2019). PEGASUS – PHYCOMORPH European Guidelines for a Sustainable Aquaculture of Seaweeds, COST Action FA1406 (Barbier M. and B. Charrier B., Eds), Roscoff, France. https://doi.org/10.21411/2c3w-yc73

- Pacto de Inovação da Bioeconomia Azul, Inovamar Lda.